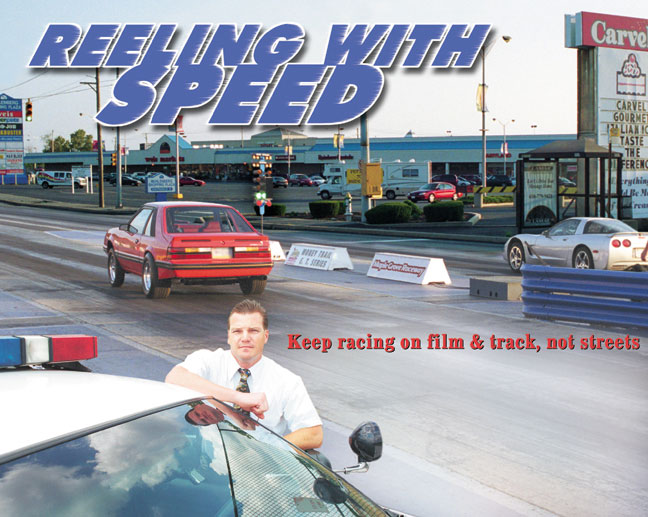

Reeling

with speed

Keep racing on

film & track not streets

By

Jeffrey Fazio

Special Sections Writer

Imagine the scene: two modified cars with extreme horsepower poised door-handle-to-door-handle at a steady red light anticipating the green, expecting the launch, ready to race ó ready to drag race on local roads. Itís an easy scene to visualize; it is right out of the 2001 movie "The Fast and the Furious." However, the frightening reality is that this scene plays itself out regularly, off screen, on real roads, with real cars, with real teenagers, with real ó very real ó deaths.

The imagery of street racing leaps from film reel to real life every day all over the country. It can be seen on local roads from California to New York; from Florida to Pennsylvania. These exhilarating contests of adrenaline and horsepower often end in violent and extraordinary crashes that are not an illusion of Hollywood. The death and destruction that result are actual. The tape cannot be rewound.

But these street contests, like the movies that depict them, are nothing new. Beyond the relatively recent movie, "The Fast and the Furious," the American moviegoer has been exposed to many other titles featuring illegal street racing over the decades, including: "Bad Boys," 1995; "The Wraith," 1986; "Heart Like a Wheel," 1983; "Grease," 1978; "American Graffiti," 1973; and "Rebel Without a Cause," 1955. Society has even found comic relief in racing scenes in movies like "Better Off Dead," 1985; "Cannonball Run II," 1984; "Cannonball Run," 1981 and "Gumball Rally," 1976.

The truth is there is no room for humor in the real world of illegal street racing. The weekend that "The Fast and The Furious" opened in theaters, there was a media frenzy over a fatal accident in Oceanside, N.Y., in which a Lamborghini Diablo was racing a Chevrolet Corvette. Michael Vasapolli, 30, the driver of the Lamborghini, crossed the center line and struck a Volvo head-on, killing himself and Glenn Jacofsky, 43, the driver of the Volvo.

Just before Christmas 2001, Dwight Samples, 21, was racing his Ford Mustang in Dona Vista, Fla. He was allegedly racing at speeds well over 100 mph when he hit a slower car in front of him, killing both occupants. Ironically, one was his mother who had bought the Mustang for him two weeks earlier.

Although these were national headlines, Berks County and the surrounding area are affected, too. This year alone, there have been several street racing incidents that have resulted in horrific crashes, causing serious injury and death:

n April 28: Charles Nelligan Jr., 26, of Phoenixville, Montgomery County, allegedly lost control of his vehicle during a street race along Route 422 near Limerick, Montgomery County, and crossed the median, hitting another vehicle and resulting in three people injured.

n March 4: Two Montgomery County men, Bradley R. Heller, 18, of Perkiomenville, and Travis A. Drumheller, 18, Pottstown, were allegedly racing between 80 and 90 mph on Route 100 in Upper Pottsgrove Township, Montgomery County, when Heller lost control of his vehicle and crossed the median and struck three other vehicles. Two passengers in Hellerís car, Jason Freed, 19, of Perkiomenville, and Adrianne Stock, 18, of Colebrookdale Township, were killed. Stephanie Ochar, 19, of Bechtelsville and a driver of one of the other vehicles, was seriously injured.

n June 13: Shawn B. Collins, 20, Alsace Township, was convicted in Berks County Court of homicide by vehicle and recklessly endangering another person in the July 2000 death of a 20-year-old Oley Township man, Michael Sipotz II.

According to Lieutenant Todd A. Graeff of the Muhlenberg Township Police Department, law enforcement is aware that some street racing does happen on Berks County roads. He explained that most local street races seem to happen between two drivers that just happen to be on the road at the same time in the same place. He went on to say that Berks County does not have the problems of arranged races that make headlines in bigger cities like Philadelphia and Los Angeles.

This speculation seems confirmed after talking with eight drivers locally that admit to racing on the street. Seven of the eight said they only race when someone else willing to race happens along. One driver did admit to occasionally going out to look for a race.

So, as the old saying goes, "It takes two to tango." Street racing, at least locally, seems to occur when drivers intent on demonstrating the performance of their cars come head to head on the street.

"I wonít turn a race down," claimed Chad, 25, of Reading, sitting in his Trans Am.

"I race whenever thereís a challenge," said Scott, 20, of Muhlenberg Township, revving the engine of his Camaro Z28.

In the last six years, Lieutenant Graeff found only two records of individuals being cited for street racing in Muhlenberg Township. Both were from this year.

In March, a driver was cited for participating in an exhibition of speed with another vehicle on the Fifth Street Highway near Muhlenberg High School. And in July, another driver was cited for racing on the highway. An officer witnessed the driver racing on the highway and/or participating in a speed contest on the Fifth Street Highway.

Assuming there is not a crash, how does a street race end?

"A race ends when you have to," said Jeff, 19, of Muhlenberg Township, sitting on the fender of his Camaro.

"A race ends when there are red and blue lights behind you," said Casey, 19, of Spring Grove, York County, who drives a Volkswagen GTI.

Many young car enthusiasts congregate along Route 222 in Muhlenberg Township during the later evening hours at hot spots like Ritaís Italian Ices, Schellís Dairy Swirl and Dairy Queen. Although these drivers are parked while they socialize and admire each otherís rides, it is easy to see they share a love of speed.

Graeff said that his department is aware of these groups. He asserted that these drivers are behaving "within a tolerable range of the vehicle code" and as long as they respect the general public and local business owners, they will not get themselves into any trouble.

The easiest way to avoid trouble on the street is to take it off the street. Berks Countians, especially those with a lead foot, have several legal and safe places to express their acceleration desires. The most notable is Maple Grove Raceway. Other venues include several events held by the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA). The SCCA holds many Solo II autocrosses in the region, as well as hosts two hill climb events each year on Duryea Drive.

For those who strictly want to demonstrate the power of their street cars, Maple Grove Raceway in Brecknock Township has a lot to offer.

George Case, vice president and general manager of Maple Grove Raceway, pointed out that people should race there because "it is a controlled atmosphere, itís legal and is much safer than racing on the street."

Case, like many drag racers, pointed out his frustration that reports of racing on the street are always labeled "drag races."

"You never hear that two people were Formula One or Indy Car racing on the street. Itís always labeled Ďdrag racing,í " explained Case. Although a lot of racing on the street does not adhere to the tenets of the sport of drag racing, all racing on the street does adhere to the legal definition of drag racing in Pennsylvania.

The Pennsylvania Vehicle Code section ß3367 defines "Drag race" as: "The operation of two or more vehicles from a point side by side at accelerating speeds in a competitive attempt to outdistance each other, or the operation of one or more vehicles over a common selected course, from the same point to the same point, for the purpose of comparing the relative speeds or power of acceleration of the vehicle or vehicles within a certain distance or time limit."

Americaís love of automobiles and of competition is the formula for a strong desire to race cars. The excitement and adrenaline of drag racing is sewn in fine threads through the fabric of American society and becomes most evident when it glares at us from exciting movie marquees and tragic newspaper headlines.